SMYRNA, Del.–When I came to Delaware to visit my mother, Emma, I found her in the early stages of dementia. There was no one to care for her but me. I had to stay. I left everything behind in Southern California. I was between apartments, my personal and household belongings were in storage. I thought I was coming for a visit. I hadn’t known I would stay so long. I didn’t even have a winter coat.

For nearly 20 years now I’ve lived in a house with my mother’s glassware, my mother’s dishes and pots and pans, my mother’s table and bath linens, my mother’s color schemes, her furniture, the flowers she chose to plant and her favorite butterfly patterns in wall art, in towels, on clothes. I have lived as a ghost in my own home.

COVID-19 relief plans and the federal stimulus have given me the funds to finally move my things out of storage and have them delivered to me.

I googled, phoned and got moving estimates. I thought I was hiring North American Van Lines to move my belongings. It turns out that this North American is North American Moving, a broker who hired Konami, a moving company I’d never heard of. I only heard of them after I had paid North American Marketing my $789 deposit on November 12, 2020.

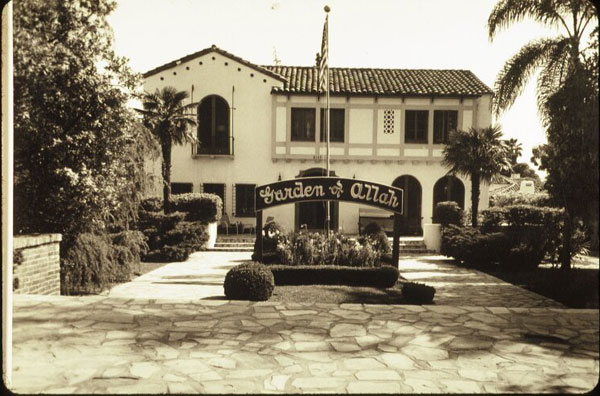

Konami Moving picked up my household belongings from a storage unit in El Segundo, California, on November 17. I paid them by credit card half the balance due, $1,157.50, per their contract. They transported my things to a warehouse in Las Vegas where the items languished for 21 days. I didn’t know this would happen. I have moved across country and up and down the East Coast, and the way it worked was that they picked up your stuff one day, put it on a truck and drove as many days as it took to traverse the distance, from door to door and delivered it, carefully placing your individual items in the rooms of your choice. Nobody took it off a truck and left it in a warehouse in a sleezy town in the middle of a desert. Needless to say, I hounded the warehouse over the phone: where are my things? what is the status? On the rare occasions I reached them, your things are in the manifest process, they said. What does this mean? How long does this take? It just depends, they don’t know, they said. The “they” being the young girls of the Tiffany generation: there’s finding a driver without COVID, there are interstate tariffs, there’s the weather, there are other deliveries, there’s….

A week went by, then two. I continually called Konami dispatch. I’d wait sometimes 45 minutes for someone to answer the phone, having to endure four bars of garbled music looping. On the rare occasions someone answered, they exhibited ennui, offhandedly telling me they had no idea where my things were, that they were with the driver and they couldn’t reach the driver because he was driving and would not answer his phone. They kept me in the dark for two months about moving status and delivery date. Over the course, I spoke with Ashley, Destiny, Amber, and one young girl who sounded like she’d just gotten out of bed after the boss’s wife caught her in the act with the boss.

During the course, Konami said they had 21 days from pickup in El Segundo to get my move on the road.

They finally told me they were loading it from the warehouse onto a truck the weekend of December 12-13, it would take five to seven days to deliver it and the driver would call me 24 hours before he arrived here.

What a joy to finally get my things—my essential self—back after all these years and before Christmas.

The driver called me on December 22 and said he’d be at my home at 8 a.m. December 23. He told me I owed a cash balance of $1,157.50. I told him I’d already paid it by credit card on December 11, to Moving Services US, when Konami wanted CASH upon delivery and I insisted I pay only by credit card. He said he’d have to call the office. He never showed. When I called dispatch they said they couldn’t reach him and didn’t know where he was. “Well, he has eight other deliveries to make,” the girl said, “and it could be the weather.” “The weather’s beautiful here and all around us and has been for days,” I told her.

I continually called Konami Moving to find out where my things were and when they would be delivered. At one call, on hearing my name, the young woman on the other end said, “Oh, I’m so sorry your things are broken and lost.” I hadn’t even seen my things, still trying to find out where they were; so, how would I know they were broken, and I hoped they were not lost.

December 28, 2020: I call Konami. Destiny says she has my number and she’s going to text the driver now. These drivers are independent contractors, it turns out, and they can make their own decisions on how long it takes to get to you. She said it could be weather related but she will get back to me today. No rain, no snow, no phone call.

January 14, 2021: Dispatch phones me from Las Vegas and tells me the driver will deliver my things the next day. The driver calls on the afternoon of the 15th and says he will be here that evening at 5:22. He and his helper arrive at 5:45, having driven the truck containing my things down from Secaucus, New Jersey, near New York City, a little over two hours north of my home in central Delaware. Had my precious, long lost belongings sat in his truck in Secaucus for a month, beneath a murky overpass? Is there anything left?

When the two guys arrive they unload my belongings on the sidewalk and grass in the dark. They insist on setting my five pieces of furniture in the living room and dumping my 50-plus cartons of books, phonograph records, china, glassware and clothing in the entrance hall, just inside the front door. The driver says he has another delivery that night, so we have to rush. He refuses to place my items in the designated rooms on all three floors, the third floor being the attic. It doesn’t have lights. He has the contract, he says, producing some crinkled, smudged papers, lays them on the sill and runs his arm over them to smooth them. “Here, this is your contract! This is your signature, right?” He waves it in my face. “It doesn’t say we have to put things in rooms.” “No, this is not my signature,” I say. “This is a copy of the legal document for pickup of my things in El Segundo, that my designated proxy there signed. Here is a copy of the contract I signed,” I say, showing him the copy in my cellphone.

The two then placed my goods in the designated rooms as best I could direct them, for they did not give me time to examine each carton to determine its contents. I instructed them to place and stack the cartons in the center of the rooms, leaving me a path to reach lamps, windows and doors. They stacked items in front of exit doors; they stacked boxes in my living room leaving me no path to get to the lamp in the corner to turn it off. The driver refused to move the boxes. Some were too heavy for me to lift. “Do you want to keep your job?” I asked the driver. “I don’t care,” he said. Finally the helper moved a few boxes to create a path to the lamp. The two were at my home until 7:45 p.m., two hours. They had stacked cartons upside down and cartons of books on top of cartons marked fragile. I have lost count of how many cup handles are broken.

Three pieces of my furniture are missing, one a family heirloom, and a fourth piece, a cabinet, has a leg splintered and broken off. I cannot repair it. My friend Joe and I set it out at the curb. One of those people who drives around in pickups looking for stuff came along and took it. Other items of value are broken or missing. My solid wood bookcase is missing. As a writer, I have a library of books and no place to shelve them. At least I have my books. I bought a new five-shelf bookcase from Amazon. I thought it would be delivered as a solid piece. It wasn’t. It came in a box full of boards and screws and nails with instructions that said to use a number 2 Phillips head screwdriver. I’m more adept at telling you what is a number 2 can of beans than a number 2 Phillips head screwdriver. Fortunately when Emma and my stepfather got divorced in their 70s, he gave her a toolbox. I found a screwdriver in there that fit. Joe is helping me assemble it. It’s taking several sessions because he has a job and other responsibilities and has to do it in his spare time.

I phoned Konami Moving in Las Vegas regarding the missing items. Amber, a young woman I had spoken to previously, upon hearing my name, said, flatly, “Yes. We got your email.” I had not sent an email. When I asked her to send me a copy, she said they couldn’t find it. She told me they do a sweep of their warehouse every Friday and IF they find my things they will call me – not whether or not, just IF. “What if they’re on one of your trucks?” I ask. She does not answer. I have not heard from them.

It happens there’s a class action lawsuit against Konami Moving and Storage with over 100 claimants, all in recent months, as well as an equal number of complaints to the Better Business Bureau, of which Konami is not a member. I have filed with both. One claimant said she actually went to the Konami Las Vegas warehouse to find her things, and found the facility strewn with beer cans and debris.

–Samantha Mozart

March 7, 2021